Dyslexia Support

in English

What is Dyslexia ?

A short history

The term “dyslexia” was first coined in 1887 in Germany and through time many definitions have been proposed and developed with a shifting focus on the root cause.

In 1896 Pringle Morgan published a description of a reading specific learning disorder titled “Congenital Word Blindness”.

In the early 1900s, James Hinshelwood asserted that the primary disability was in visual memory for words and letters and difficulty in naming visual objects.

In 1930, Samuel Orton used the term ‘strephosymbolia’ (meaning twisted signs) to define the fact that these children often showed difficulties with reversals/orientation. However, he observed that dyslexia did not stem from strictly visual deficits and believed the condition was caused by the failure to establish hemispheric dominance in the brain. He looked for a way to teach reading using both left and right brain functions and with Anna Gillingham developed the famous Orton Gillingham approach that pioneered the use of simultaneous multisensory instruction.

In the 70s, Vellutino argued that dyslexia should not be considered a perceptual deficit, but a sound based verbal deficit. In the 80s, the phonological deficit model became widely accepted, which helped explain difficulties that children with dyslexia face with phonological awareness, rapid naming, verbal short-term memory, and verbal learning (letters, digits).

Towards the end of the 20th century, research into dyslexia also focused on difficulties with automatic balance and immature motor skills. In 1996, Fawcett and Nicholson concluded that “children with dyslexia have difficulties with phonological skill, speed of processing and motor skills”.

In 2002, Talcott and al. reported that both visual motion sensitivity and auditory sensitivity to frequency differences were strong predictors of children’s literacy skills and their orthographic and phonological skills.

In recent years, neuroimaging technologies have allowed for a better understanding of the areas of the brain involved in efficient reading and current models of the relation between the brain and dyslexia focus on some form of delayed brain maturation.

Today, according to the BDA (British dyslexia Association), at least 10% of the population are believed to be dyslexic. The BDA has adopted Tim Rose’s description of dyslexia (2009), and this is the one frequently quoted in children’s dyslexia assessment reports:

Dyslexia is a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. Characteristic features of dyslexia, are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed. Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities. It is best thought of as a continuum, not a distinct category, and there are no clear cut off points . Co-occurring difficulties may be seen in aspects of language, motor coordination, mental calculation, concentration and personal organization, but these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia. A good indication of the severity and persistence of dyslexic difficulties can be gained by examining how the individual responds or has responded to well-founded intervention.

In addition to these characteristics, the British dyslexia Association (since 2010) “acknowledges the visual and auditory processing difficulties that some children with dyslexia can experience”.

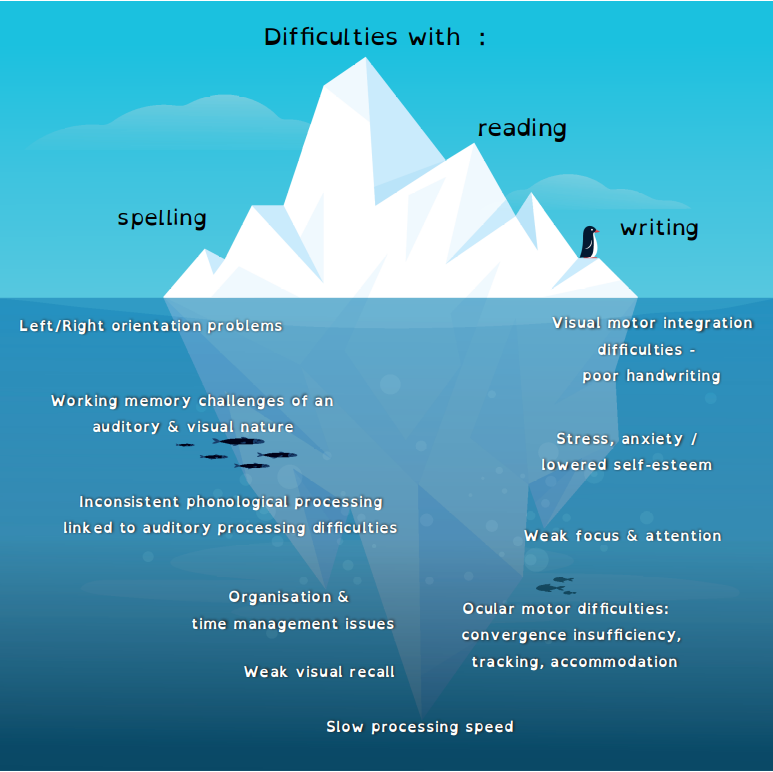

Dyslexia is indeed an umbrella term and every dyslexic individual presents with a differing combination of underlying issues below the surface of the easily observed unexpected difficulties with reading, writing and spelling. Many of the underlying causes/symptoms have a physiological basis.

The dyslexia iceberg provides an excellent analogy of this:

At the Motorway Kids, physiological issues are not only ackknowledged, but addressed. Integration of the primitive reflexes and development of the postural reflexes mature the central nervous system with concomitant improvements in motor coordination, body awareness and concentration. The Moro, TLR, ATNR and STNR are the main reflexes affecting occular motor functioning. In order for the eyes to be able to fixate, track, converge and accomodate well, these reflexes need to be integrated. Please refer to the section on the main reflexes.

Auditory processing difficulties, giving rise to issues with phonological processing, auditory attention and processing speed are also adressed at the Motorway Kids. Please refer to the section on Listening Therapy.

Made by Dyslexia give the following 10 points that you need to know about dyslexia:

Dyslexia Support in English at the Motorway Kids

At the Motorway Kids, we too believe in the importance of identification of and support for children with dyslexic difficulties. No formal diagnosis of dyslexia can be given, but a very comprehensive screener may be administered, giving standardized scores for phonological processing, working memory and processing speed, areas of functioning that are all dyslexia sensitive. The results are processed to give a dyslexia index of A-E.

Standardized, tests of single word spelling and reading may also be carried out, giving reliable performance scores in these areas. In addition, an assessment of passage reading, giving standardized scores for reading accuracy, rate and comprehension can be offered.

Intervention is proposed in hourly sessions, using a range of materials from a variety of leading programs specifically tailored to meet the needs of the individual child. Lessons always incorporate the 3 elements critical for success with children with a dyslexic profile:

- structure,

- multi-sensory input and

- opportunities for the required amount of over-learning.

NB: Children receiving Learning Support for literacy/ dyslexic difficulties at the British School of Paris are not eligible for this kind of support with the Motorway Kids. However INPP reflex integration and Tomatis and Johansen listening therapies are accessible to all.

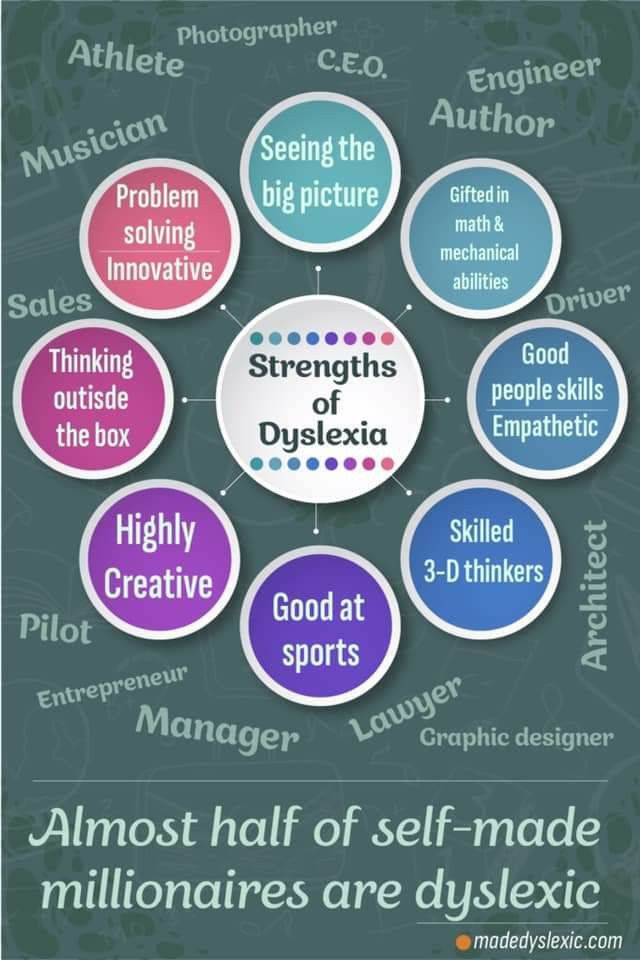

Acknowledging the Dyslexic difference to restore self-confidence

Children with dyslexia, tend to have very spiky profiles of performance, being in the top percentile in certain areas -communication, problem solving and creativity and the bottom in others, spelling and reading and memorizing facts. In school, a lot of emphasis is placed on and evaluations are carried out in areas that dyslexic individuals find more challenging, which can lead children into believing themselves to be ‘stupid’ and experiencing the low self-esteem that this engenders. However, the brain of dyslexic individuals are simply wired differently. It is a difference, not a deficit.

Kate Griggs, CEO of the charity Made By Dyslexia has been shifting the narrative on dyslexia and educating people on its strengths. She claims that those things that dyslexic individuals are not good at, technology can now do.

Made by Dyslexia list the many positive thinking skills people with dyslexia often possess:

- Reasoning: Understanding patterns, evaluating possibilities and making decisions (84% of dyslexics are above average in Reasoning).

- Communicating: Crafting and conveying clear and engaging messages (71% of dyslexics are above average at Communicating).

- Imagining: Creating an original piece of work, or giving ideas a new spin (84% of dyslexics are above average at Imagining).

- Exploring: Being curious and exploring ideas in a constant energetic way (84% of dyslexics are above average at Exploring).

- Connecting: Understanding self -connecting, empathizing and influencing others (80% of dyslexics are above average at Connecting).

- Visualizing: Interacting with space, senses, physical ideas, and new concepts (75% of dyslexics are above average at Visualizing).

Thanks to the efforts of this charity, a new, more positive definition of dyslexia has been included in the dictionary and Dyslexic thinking can be added as a skill on Linked in profiles.

CONTACT

Have any questions? I am always open to talk about your children and how I can help you.